Do Schools Pay More for Math and Science Than Arts and Literature

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cd/ee/cdee1c82-f8e3-4de4-983e-8599d4485745/finland-smiles-wr.jpg)

It was the end of term at Kirkkojarvi Comprehensive School in Espoo, a sprawling suburb west of Helsinki, when Kari Louhivuori, a veteran teacher and the school'south principal, decided to endeavor something extreme—past Finnish standards. One of his sixth-course students, a Kosovo-Albanian boy, had drifted far off the learning grid, resisting his teacher's all-time efforts. The school's team of special educators—including a social worker, a nurse and a psychologist—convinced Louhivuori that laziness was not to blame. So he decided to concur the male child dorsum a year, a measure so rare in Finland it'south practically obsolete.

Finland has vastly improved in reading, math and scientific discipline literacy over the past decade in big part because its teachers are trusted to do any it takes to turn immature lives around. This 13-year-one-time, Besart Kabashi, received something akin to royal tutoring.

"I took Besart on that year equally my private student," Louhivuori told me in his function, which boasted a Beatles "Yellow Submarine" poster on the wall and an electric guitar in the cupboard. When Besart was not studying scientific discipline, geography and math, he was parked side by side to Louhivuori'due south desk-bound at the forepart of his class of 9- and 10-year- olds, cracking open books from a alpine stack, slowly reading one, so another, then devouring them by the dozens. By the end of the twelvemonth, the son of Kosovo war refugees had conquered his adopted land'south vowel-rich linguistic communication and arrived at the realization that he could, in fact, learn.

Years subsequently, a xx-year-erstwhile Besart showed up at Kirkkojarvi's Christmas political party with a bottle of Cognac and a large grin. "You helped me," he told his erstwhile teacher. Besart had opened his own car repair firm and a cleaning company. "No big fuss," Louhivuori told me. "This is what we do every day, fix kids for life."

This tale of a single rescued child hints at some of the reasons for the tiny Nordic nation'south staggering record of teaching success, a miracle that has inspired, baffled and even irked many of America'south parents and educators. Finnish schooling became an unlikely hot topic after the 2010 documentary motion-picture show Waiting for "Superman" contrasted it with America'south troubled public schools.

"Whatever it takes" is an attitude that drives not just Kirkkojarvi's xxx teachers, but well-nigh of Republic of finland's 62,000 educators in 3,500 schools from Lapland to Turku—professionals selected from the height ten percent of the nation's graduates to earn a required primary'southward degree in education. Many schools are pocket-sized enough and so that teachers know every educatee. If one method fails, teachers consult with colleagues to try something else. They seem to relish the challenges. Nearly xxx percent of Finland'due south children receive some kind of special assist during their first 9 years of school. The school where Louhivuori teaches served 240 outset through ninth graders last twelvemonth; and in contrast with Finland's reputation for ethnic homogeneity, more than than half of its 150 unproblematic-level students are immigrants—from Somalia, Republic of iraq, Russia, Bangladesh, Estonia and Federal democratic republic of ethiopia, amongst other nations. "Children from wealthy families with lots of education can be taught by stupid teachers," Louhivuori said, smiling. "Nosotros effort to grab the weak students. Information technology's deep in our thinking."

The transformation of the Finns' didactics system began some 40 years agone as the key propellent of the country's economic recovery plan. Educators had little idea it was then successful until 2000, when the first results from the Plan for International Student Assessment (PISA), a standardized test given to fifteen-yr-olds in more than 40 global venues, revealed Finnish youth to be the all-time young readers in the globe. Three years later, they led in math. By 2006, Finland was first out of 57 countries (and a few cities) in science. In the 2009 PISA scores released concluding year, the nation came in second in science, third in reading and sixth in math among well-nigh one-half a million students worldwide. "I'm even so surprised," said Arjariita Heikkinen, principal of a Helsinki comprehensive school. "I didn't realize we were that practiced."

In the United States, which has muddled along in the middle for the past decade, government officials have attempted to introduce marketplace contest into public schools. In contempo years, a group of Wall Street financiers and philanthropists such as Pecker Gates accept put coin behind private-sector ideas, such as vouchers, information-driven curriculum and lease schools, which have doubled in number in the past decade. President Obama, too, has apparently bet on competition. His Race to the Summit initiative invites states to compete for federal dollars using tests and other methods to measure teachers, a philosophy that would not fly in Republic of finland. "I think, in fact, teachers would tear off their shirts," said Timo Heikkinen, a Helsinki principal with 24 years of teaching experience. "If y'all but measure the statistics, you lot miss the human aspect."

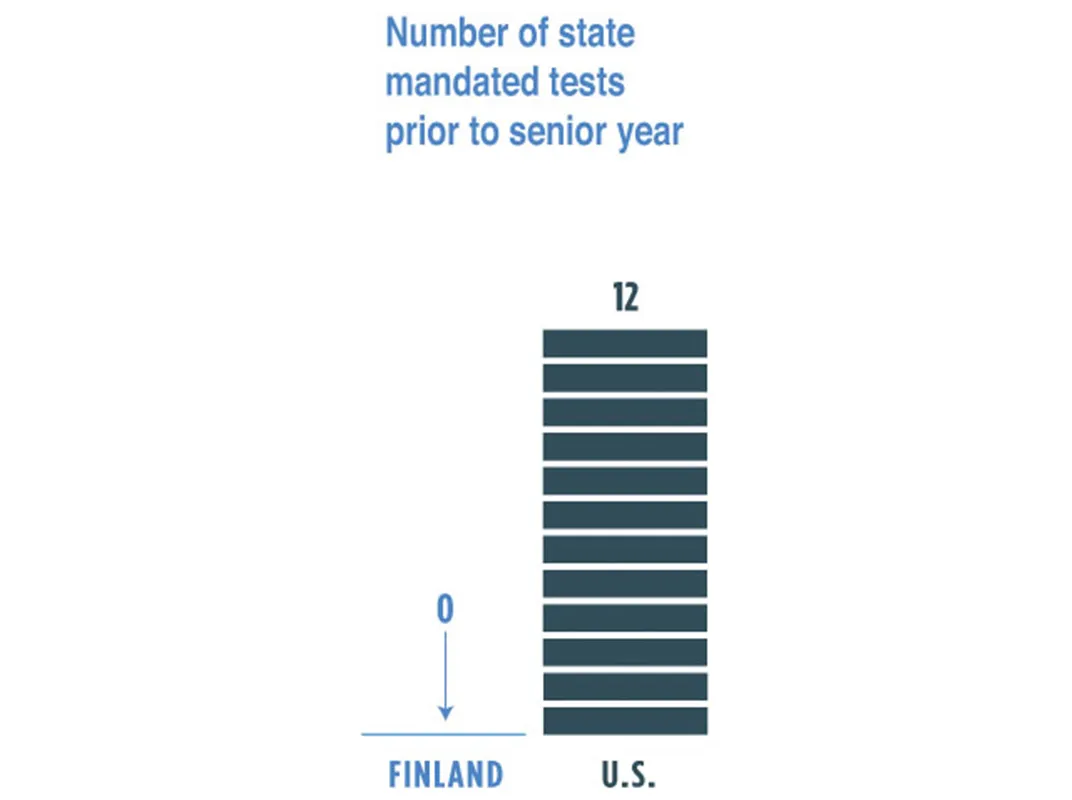

There are no mandated standardized tests in Republic of finland, apart from one examination at the end of students' senior yr in high school. At that place are no rankings, no comparisons or competition betwixt students, schools or regions. Finland's schools are publicly funded. The people in the government agencies running them, from national officials to local government, are educators, not business people, armed services leaders or career politicians. Every school has the same national goals and draws from the same pool of university-trained educators. The result is that a Finnish child has a good shot at getting the same quality education no matter whether he or she lives in a rural hamlet or a academy town. The differences betwixt weakest and strongest students are the smallest in the globe, according to the virtually recent survey by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). "Equality is the nigh important word in Finnish education. All political parties on the correct and left concur on this," said Olli Luukkainen, president of Finland'due south powerful teachers union.

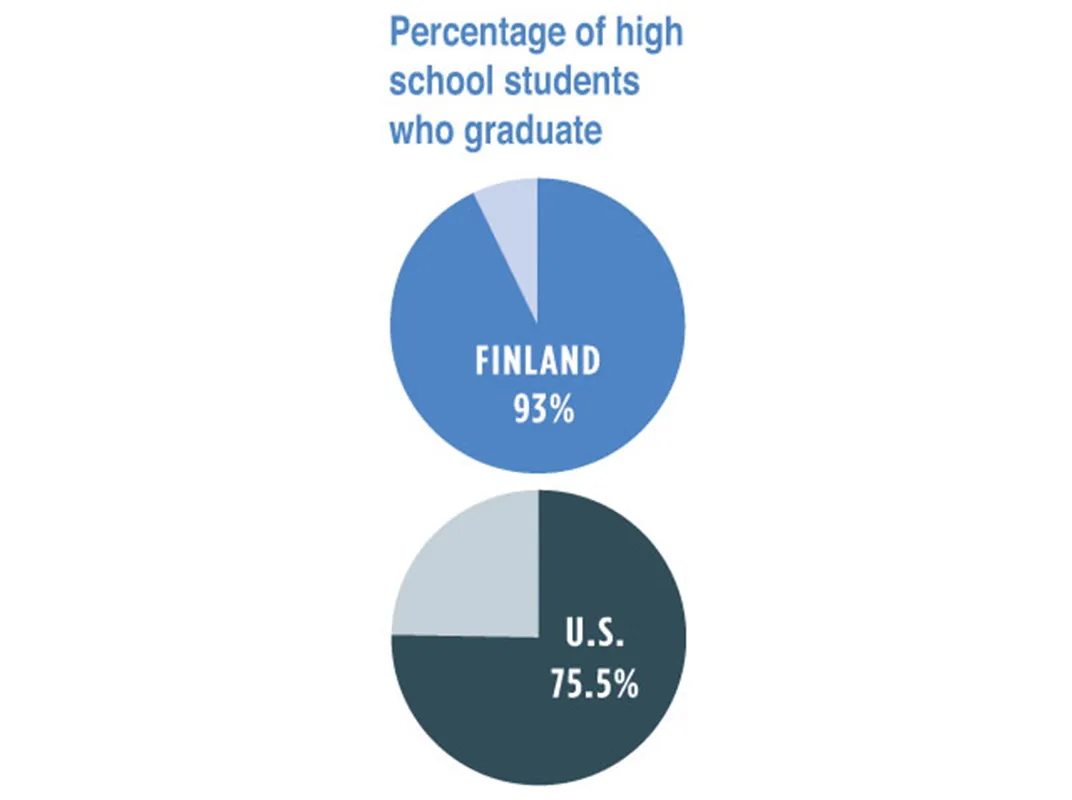

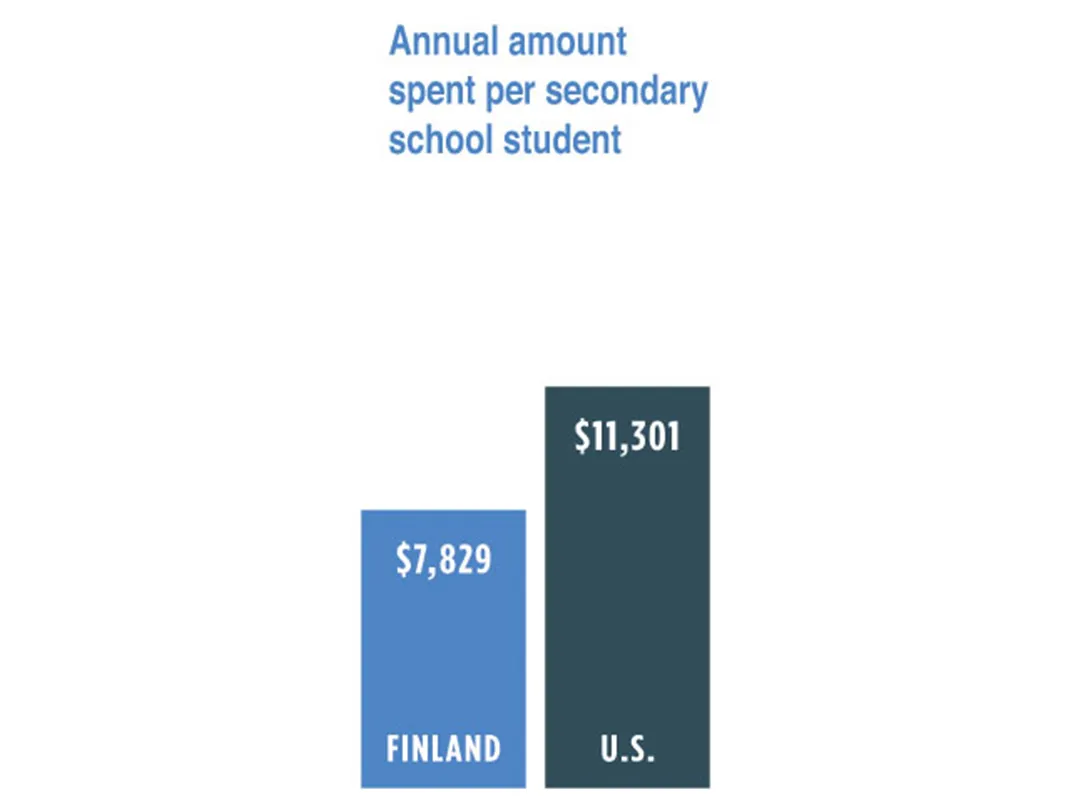

Ninety-three percent of Finns graduate from academic or vocational high schools, 17.5 percentage points higher than the U.s.a., and 66 percent keep to college educational activity, the highest charge per unit in the Eu. Yet Finland spends nigh thirty percent less per student than the United states of america.

Yet, there is a distinct absence of chest-thumping among the famously reticent Finns. They are eager to celebrate their recent world hockey championship, merely PISA scores, not and then much. "We prepare children to learn how to learn, not how to accept a test," said Pasi Sahlberg, a former math and physics teacher who is at present in Republic of finland's Ministry building of Instruction and Civilisation. "We are not much interested in PISA. Information technology'southward not what we are about."

Maija Rintola stood before her chattering class of xx-iii seven- and viii-year-olds ane late April day in Kirkkojarven Koulu. A tangle of multicolored threads topped her copper pilus like a painted wig. The 20-year teacher was trying out her look for Vappu, the day teachers and children come up to school in riotous costumes to celebrate May Day. The morning sun poured through the slate and lemon linen shades onto containers of Easter grass growing on the wooden sills. Rintola smiled and held up her open hand at a slant—her time-tested "silent giraffe," which signaled the kids to exist quiet. Little hats, coats, shoes stowed in their cubbies, the children wiggled next to their desks in their stocking feet, waiting for a plow to tell their tale from the playground. They had but returned from their regular xv minutes of playtime outdoors between lessons. "Play is important at this age," Rintola would later on say. "We value play."

With their wiggles unwound, the students took from their desks niggling numberless of buttons, beans and laminated cards numbered i through 20. A teacher's aide passed effectually yellow strips representing units of ten. At a smart board at the front of the room, Rintola ushered the class through the principles of base of operations x. One girl wore cat ears on her head, for no apparent reason. Another kept a stuffed mouse on her desk to remind her of home. Rintola roamed the room helping each child grasp the concepts. Those who finished early played an advanced "nut puzzle" game. After 40 minutes it was fourth dimension for a hot lunch in the cathedral-like cafeteria.

Teachers in Finland spend fewer hours at schoolhouse each day and spend less time in classrooms than American teachers. Teachers use the extra time to build curriculums and assess their students. Children spend far more fourth dimension playing outside, even in the depths of wintertime. Homework is minimal. Compulsory schooling does not brainstorm until historic period 7. "We have no hurry," said Louhivuori. "Children learn ameliorate when they are fix. Why stress them out?"

Information technology's almost unheard of for a child to show up hungry or homeless. Republic of finland provides three years of maternity go out and subsidized day intendance to parents, and preschool for all 5-year-olds, where the emphasis is on play and socializing. In add-on, the state subsidizes parents, paying them effectually 150 euros per month for every child until he or she turns 17. Ninety-seven percent of six-year-olds attend public preschool, where children begin some academics. Schools provide food, medical care, counseling and taxi service if needed. Student health care is free.

Yet, Rintola said her children arrived terminal August miles apart in reading and language levels. Past April, nearly every kid in the class was reading, and most were writing. Boys had been coaxed into literature with books like Kapteeni Kalsarin ("Captain Underpants"). The school's special education teacher teamed upward with Rintola to teach five children with a diversity of behavioral and learning problems. The national goal for the past five years has been to mainstream all children. The simply time Rintola's children are pulled out is for Finnish as a 2nd Language classes, taught past a teacher with 30 years' feel and graduate school training.

There are exceptions, though, nonetheless rare. One first-grade girl was not in Rintola's class. The wispy vii-year-quondam had recently arrived from Thailand speaking not a word of Finnish. She was studying math down the hall in a special "preparing grade" taught by an skillful in multicultural learning. It is designed to help children keep up with their subjects while they conquer the language. Kirkkojarvi'south teachers have learned to bargain with their unusually large number of immigrant students. The city of Espoo helps them out with an extra 82,000 euros a year in "positive discrimination" funds to pay for things like special resources teachers, counselors and 6 special needs classes.

Rintola will teach the same children next year and possibly the next 5 years, depending on the needs of the school. "It's a good system. I tin can make stiff connections with the children," said Rintola, who was handpicked by Louhivuori 20 years ago. "I sympathize who they are." Too Finnish, math and scientific discipline, the first graders accept music, art, sports, religion and textile handcrafts. English begins in tertiary grade, Swedish in fourth. Past fifth class the children have added biology, geography, history, physics and chemical science.

Not until sixth grade volition kids have the option to sit for a commune-wide examination, and then only if the classroom instructor agrees to participate. Virtually do, out of curiosity. Results are not publicized. Finnish educators have a hard time understanding the United States' fascination with standardized tests. "Americans like all these bars and graphs and colored charts," Louhivuori teased, equally he rummaged through his cupboard looking for past years' results. "Looks like we did better than boilerplate two years agone," he said subsequently he institute the reports. "It's nonsense. We know much more about the children than these tests can tell us."

I had come to Kirkkojarvi to see how the Finnish approach works with students who are non stereotypically blond, blueish-eyed and Lutheran. Merely I wondered if Kirkkojarvi's success confronting the odds might be a fluke. Some of the more vocal conservative reformers in America take grown weary of the "We-Love-Finland crowd" or so-called Finnish Green-eyed. They argue that the U.s.a. has little to learn from a country of but v.4 meg people—four per centum of them foreign born. However the Finns seem to exist onto something. Neighboring Norway, a country of similar size, embraces education policies similar to those in the United States. Information technology employs standardized exams and teachers without master'south degrees. And like America, Norway's PISA scores have been stalled in the middle ranges for the better part of a decade.

To become a 2d sampling, I headed eastward from Espoo to Helsinki and a rough neighborhood called Siilitie, Finnish for "Hedgehog Route" and known for having the oldest low-income housing projection in Finland. The 50-yr-old indigestible school building sabbatum in a wooded area, effectually the corner from a subway end flanked past gas stations and convenience stores. Half of its 200 first- through ninth-form students accept learning disabilities. All simply the most severely impaired are mixed with the full general education children, in keeping with Finnish policies.

A course of start graders scampered among nearby pine and birch trees, each belongings a stack of the teacher'southward homemade laminated "outdoor math" cards. "Discover a stick as big as your pes," 1 read. "Assemble 50 rocks and acorns and lay them out in groups of ten," read another. Working in teams, the vii- and 8-year-olds raced to see how rapidly they could carry out their tasks. Aleksi Gustafsson, whose master's degree is from Helsinki University, developed the exercise after attending one of the many workshops available gratuitous to teachers. "I did research on how useful this is for kids," he said. "Information technology's fun for the children to work outside. They really learn with it."

Gustafsson'south sister, Nana Germeroth, teaches a form of mostly learning-impaired children; Gustafsson'southward students accept no learning or behavioral issues. The ii combined about of their classes this year to mix their ideas and abilities along with the children'southward varying levels. "We know each other really well," said Germeroth, who is ten years older. "I know what Aleksi is thinking."

The schoolhouse receives 47,000 euros a yr in positive discrimination money to hire aides and special education teachers, who are paid slightly college salaries than classroom teachers because of their required 6th yr of university preparation and the demands of their jobs. There is one teacher (or assistant) in Siilitie for every vii students.

In another classroom, two special educational activity teachers had come up with a unlike kind of team teaching. Last year, Kaisa Summa, a teacher with five years' experience, was having trouble keeping a gaggle of first-class boys under control. She had looked longingly into Paivi Kangasvieri'south quiet second-class room side by side door, wondering what secrets the 25-year-veteran colleague could share. Each had students of wide-ranging abilities and special needs. Summa asked Kangasvieri if they might combine gymnastics classes in hopes good behavior might exist contagious. It worked. This year, the two decided to merge for sixteen hours a week. "We complement each other," said Kangasvieri, who describes herself every bit a calm and firm "father" to Summa's warm mothering. "It is cooperative teaching at its all-time," she says.

Every so often, principal Arjariita Heikkinen told me, the Helsinki district tries to close the school because the surrounding area has fewer and fewer children, but to have people in the community rise up to save it. Afterward all, virtually 100 per centum of the school's 9th graders keep to high schools. Fifty-fifty many of the about severely disabled volition find a place in Finland's expanded system of vocational high schools, which are attended by 43 percent of Finnish high-schoolhouse students, who prepare to work in restaurants, hospitals, construction sites and offices. "We help situate them in the right loftier school," said then deputy principal Anne Roselius. "We are interested in what will get of them in life."

Finland's schools were not ever a wonder. Until the late 1960s, Finns were still emerging from the cocoon of Soviet influence. Near children left public school after six years. (The rest went to private schools, academic grammar schools or folk schools, which tended to be less rigorous.) Only the privileged or lucky got a quality education.

The landscape inverse when Finland began trying to remold its bloody, fractured past into a unified hereafter. For hundreds of years, these fiercely independent people had been wedged between two rival powers—the Swedish monarchy to the west and the Russian czar to the eastward. Neither Scandinavian nor Baltic, Finns were proud of their Nordic roots and a unique linguistic communication simply they could love (or pronounce). In 1809, Finland was ceded to Russia by the Swedes, who had ruled its people some 600 years. The czar created the Grand Duchy of Republic of finland, a quasi-land with ramble ties to the empire. He moved the capital from Turku, near Stockholm, to Helsinki, closer to Petrograd. After the czar fell to the Bolsheviks in 1917, Finland alleged its independence, pitching the country into civil war. 3 more wars between 1939 and 1945—ii with the Soviets, one with Frg—left the country scarred by biting divisions and a punishing debt owed to the Russians. "Still we managed to keep our freedom," said Pasi Sahlberg, a director general in the Ministry of Education and Civilization.

In 1963, the Finnish Parliament made the bold determination to choose public education as its all-time shot at economic recovery. "I telephone call this the Big Dream of Finnish education," said Sahlberg, whose upcoming book,Finnish Lessons, is scheduled for release in October. "It was but the idea that every child would have a very skilful public school. If we want to exist competitive, nosotros need to educate everybody. Information technology all came out of a need to survive."

Practically speaking—and Finns are nothing if non practical—the conclusion meant that goal would non be allowed to dissipate into rhetoric. Lawmakers landed on a deceptively simple plan that formed the foundation for everything to come. Public schools would be organized into one organisation of comprehensive schools, orperuskoulu, for ages 7 through 16. Teachers from all over the nation contributed to a national curriculum that provided guidelines, not prescriptions. Too Finnish and Swedish (the country'south second official linguistic communication), children would larn a tertiary language (English is a favorite) usually first at historic period 9. Resources were distributed as. As the comprehensive schools improved, so did the upper secondary schools (grades 10 through 12). The second critical decision came in 1979, when reformers required that every instructor earn a fifth-year master's caste in theory and practice at one of viii state universities—at state expense. From then on, teachers were finer granted equal status with doctors and lawyers. Applicants began flooding teaching programs, non because the salaries were and so high but because autonomy and respect fabricated the task attractive. In 2010, some 6,600 applicants vied for 660 primary schoolhouse grooming slots, co-ordinate to Sahlberg. Past the mid-1980s, a final set of initiatives shook the classrooms gratis from the last vestiges of top-down regulation. Command over policies shifted to town councils. The national curriculum was distilled into broad guidelines. National math goals for grades one through nine, for case, were reduced to a neat ten pages. Sifting and sorting children into and so-chosen power groupings was eliminated. All children—clever or less and then—were to be taught in the same classrooms, with lots of special teacher assist available to brand sure no child really would be left backside. The inspectorate airtight its doors in the early '90s, turning accountability and inspection over to teachers and principals. "We have our own motivation to succeed because we beloved the piece of work," said Louhivuori. "Our incentives come from within."

To be sure, information technology was only in the by decade that Finland's international science scores rose. In fact, the country'southward earliest efforts could exist called somewhat Stalinistic. The first national curriculum, adult in the early on '70s, weighed in at 700 stultifying pages. Timo Heikkinen, who began teaching in Finland'due south public schools in 1980 and is now principal of Kallahti Comprehensive Schoolhouse in eastern Helsinki, remembers when nearly of his loftier-school teachers sat at their desks dictating to the open notebooks of compliant children.

And there are still challenges. Finland's crippling fiscal collapse in the early '90s brought fresh economic challenges to this "confident and believing Eurostate," as David Kirby calls information technology inA Concise History of Finland. At the aforementioned time, immigrants poured into the country, clustering in low-income housing projects and placing added strain on schools. A contempo report by the Academy of Finland warned that some schools in the country's large cities were becoming more than skewed past race and class as flush, white Finns choose schools with fewer poor, immigrant populations.

A few years ago, Kallahti main Timo Heikkinen began noticing that, increasingly, affluent Finnish parents, peradventure worried about the rising number of Somali children at Kallahti, began sending their children to one of two other schools nearby. In response, Heikkinen and his teachers designed new environmental science courses that take advantage of the school's proximity to the forest. And a new biology lab with iii-D applied science allows older students to notice blood flowing inside the man body.

It has even so to catch on, Heikkinen admits. Then he added: "But we are always looking for ways to improve."

In other words, any information technology takes.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/why-are-finlands-schools-successful-49859555/

Post a Comment for "Do Schools Pay More for Math and Science Than Arts and Literature"